10 February 2026

The Government has submitted Draft Law No. 47/XVII/1.ª to Parliament. This legislative initiative provides for a set of tax incentives aimed at stimulating the supply of affordably priced housing for the middle class.

There are two amounts that need to be set: €2,300 and €660,982.

These are the maximum amounts proposed in 2026 for “moderate monthly rent” and “moderate sale price,” and it is around these amounts that a significant part of the incentives revolves.

Namely, developers who ‘build to sell for up to €660,982’ or ‘build to rent for up to €2,300’ benefit from a reduction in VAT from 23% to 6%.

In the case of renting, €2,300 is also the maximum amount eligible for a reduction in the taxation of property income earned by landlords.

The bill is already being discussed in detail.

The purpose of this text is to help readers understand some of these measures and their relevance. And, if possible, to make the Government aware of the importance of reviewing some of the points in its proposal.

[If you prefer, you may access the short version of this article, which immediately sets out the main objections to the draft law.]

How was the maximum value of a moderate rent defined?

According to Draft Law no. 47/XVII/1.ª, this amount corresponds to “2.5 times the value of the monthly minimum wage set for 2026.”

Since the minimum wage defined for that year is €920, the maximum limit for a rent to be considered moderate is €2,300.

One of the most frequent objections is that €2,300 is an excessively high rent — excessively high, that is, to qualify for a tax reduction.

But for what level of income would a rent of €2,300 be sustainable?

I used the Doutor Finanças simulator to estimate the net salary of a married individual with two dependents, considering a base salary of €4,185.07 and additional compensation of €418.51 (that is, the gross monthly salary and representation allowance of a Member of the Portuguese Parliament working on an exclusive basis, in 2025).

The result was approximately €2,900 net. Assuming two spouses earning this same income, the household would receive around €5,800 net.

This means that a rent of €2,100, €2,200, or €2,300 would represent an effort rate of 36.2%, 37.9%, and 39.7%, respectively, for a couple whose individual gross income is comparable to the base salary of a Member of Parliament.

For reference, another measure — the Extraordinary Rent Support — was designed with reference to “a maximum effort rate of 35%,” above which the State provides support to households.

In other words, in 2023, within the same sphere of public housing policy, the 35% threshold (which is exceeded in all three scenarios above) was established as the point beyond which housing-related financial effort is considered excessive.

The Government has responded to criticism by noting that:

- Contrary to what has been suggested by some voices, this measure will not contribute to a generalized increase in rents up to €2,300.

- The minimum and maximum amounts for a moderate rent are €400 and €2,300, respectively; therefore, all values between these two limits fall within the scope of the measure.

- Considering market values in Lisbon, Porto, and some neighboring municipalities within their respective metropolitan areas, the €2,300 limit is appropriate for a concept of moderate value.

I agree that, in the short term, the most plausible outcome is that this tax incentive will translate into a reduction to €2,300 of rents that currently sit just above this maximum threshold. In light of the current wording of the draft law, it is plausible that this may occur both in new contracts and in ongoing contracts, where the landlord proposes a rent reduction to the tenant in a mutually beneficial arrangement. We may debate whether this is the price range that should concern us most, but realistically, this is the most likely immediate effect.

On the other hand, it seems evident to me that the apparent consensus regarding the range of values between €400 and €2,300 does not, in itself, explain its upper limit. Questioning that limit is a useful exercise. And the more I hear the Government justify a maximum value applied uniformly across 308 municipalities with the response that “in Lisbon, €2,300 is a moderate amount,” the stronger the impression that this exercise may not have been taken seriously enough.

The Government may argue that a transversal measure, applied without territorial restrictions, is easier to implement and communicate. It may also contend that this could make an important contribution to combating tax evasion, encouraging landlords who currently do not report contracts to the Tax and Customs Authority to regularize their situation. Or even, in areas under greater urban pressure, attract property owners who currently operate in the short-term rental market.

It may also suggest that the same measures that have generated controversy are precisely those capable of capturing the attention of sector entrepreneurs — and that without their confidence, it will be difficult to significantly increase housing supply.

In essence, all of this is true. But as we shall see, there are other relevant criteria that the Government may not be taking into account.

.jpeg)

What benefit is granted to landlords who charge rents of up to €2,300?

According to the Government’s draft law:

- “The application of a reduced autonomous IRS tax rate of 10% to rental income arising from lease agreements intended for residential purposes.”

- “For IRC purposes, the consideration of rental income arising from lease agreements intended for residential purposes at 50%.”

I do not believe it is possible to discuss this matter without the following reflection: according to the DataLABOR simulator, a single worker with no dependents earning a base salary of €1,615 — which, according to Statistics Portugal (INE), corresponds to the average gross total monthly remuneration per worker in Portugal — is subject to a 12% IRS withholding rate. If that same person’s base salary increases to €2,000, the withholding rate rises to 15%.

I imagine that most people would feel some discomfort at the idea that labor income may be subject to higher taxation than rental income, even when the rents in question exceed wage levels.

On the other hand, we are living through a housing access crisis. To define this issue as a priority is precisely that: to treat it preferentially relative to others.

Considering the production cycle of a property (or even its rehabilitation), bringing vacant dwellings onto the rental market will always be the fastest way to increase housing supply.

According to the 2021 Census, 8% of the housing stock in Lisbon and Porto consists of dwellings classified as “vacant for other reasons.” According to INE, this means they are neither anyone’s primary or secondary residence, nor available for sale or rent.

It is not known how many of these 25,999 homes in Lisbon and 10,660 in Porto (248,534 nationwide) are, in fact, in the material and legal condition required to be placed on the market. Yet it is precisely this pool of dwellings that the Government proposes to mobilize.

Diário da República, 1.ª série — N.º 109 — 6 de junho de 2019

What added value does this new benefit bring to the current framework?

Rental income from residential properties is currently taxed at a flat autonomous rate of 25% under IRS, with the following rate reductions depending on the duration of the contract:

- A 10% reduction for contracts lasting five years or more and less than ten years.

This means that a five-year contract may be taxed at 15%.

- A 15% reduction for contracts lasting ten years or more and less than twenty years.

This means that a ten-year contract may be taxed at 10%.

- A 20% reduction for contracts lasting twenty years or more.

This means that a twenty-year contract may be taxed at 5%.

However, there is a condition for these reductions to apply.

The rent in question may not exceed by more than 50% the “general rent price limits by typology” applicable under the Affordable Rental Programme, which were defined in 2019 according to a six-tier municipal matrix set out in Table 1 (annexed to Ministerial Order no. 176/2019, whose amounts, it should be noted, “may be updated annually”).

With this framework, the previous Government sought to ensure two things:

- A significant tax discount for landlords who prioritize contracts lasting five years or more (considering this a sufficient period to provide stability for families);

- An adjustment of rent limits — by municipality and by typology — to the granting of that tax benefit; that is, the applicable limits in Alandroal and Miranda do Corvo are not the same as those in Lisbon or Porto, nor, within the same municipality, is a studio (T0) treated the same as a four-bedroom apartment (T4).

It should be noted that the amounts set out in Table 2 were defined in 2019 based on the median rents in each municipality as published by Statistics Portugal (INE), and have since been updated.

Looking at the table published on the Housing Portal (which lists the maximum rents allowed in 2025), the owner of a three-bedroom apartment in Lisbon who rented it last year for €2,250 would already pay only 15% tax on rental income (5 percentage points more than what the Government is now proposing), provided that a five-year contract had been signed.

When we examine the 2025 table, we understand that:

- For the Lisbon market, the current Government’s proposal is largely aligned with the existing tax framework. It represents what could be described as an additional incentive.

- From a technical standpoint, it is very difficult to justify applying a single benchmark — presumably suited to Lisbon’s reality — to a territorial universe of 308 municipalities.

But does this mean that the existing regime would already be sufficient?

I believe not.

For example, previous measures stipulated that if a contract were terminated “for reasons attributable to the landlord,” the landlord would have to repay the amounts corresponding to the tax reduction previously obtained.

At first glance, this rule appears coherent. However, considering that the landlord has merery the right to oppose the renewal of a contract — while only the tenant has the right to terminate it (Articles 1097 and 1098 of the Civil Code) — its application creates a paradoxical situation.

A landlord who signs a five-year renewable contract and subsequently opposes its renewal for a new term is required to repay the tax benefit received.

By contrast, a landlord who signs a five-year non-renewable contract — an option also provided for in Article 1096 — fully retains the right to the tax reduction.

I do not believe this difference in tax treatment makes any sense.

Diário da República, 1.ª série — N.º 109 — 6 de junho de 2019

How is the construction of housing at moderate sale and rental prices intended to be encouraged?

One of the most emblematic measures in this draft law is the reduction of VAT from 23% to 6% for the development of housing that is made available for rent and sale at prices up to €2,300 and €660,982, respectively.

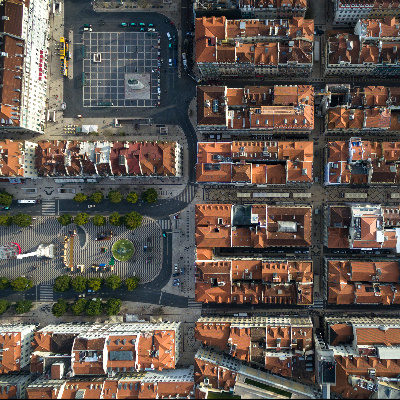

The reduction of VAT on construction had been requested by the sector for some time and is, in a way, inspired by the precedent set with the approval of the 2009 State Budget, which provided for the application of the reduced VAT rate to urban rehabilitation works. There is currently a broad consensus regarding the positive contribution of that legislative initiative to the rehabilitation of historic city centers, particularly in Lisbon and Porto.

With this incentive, the Government expects to encourage residential construction and rehabilitation at values deemed moderate, and to contribute to an increase in the number of dwellings available for sale and rent.

But should the Government’s draft law be applied as currently designed?

In my view, it should not.

Why?

There are three unavoidable inconsistencies.

And I would argue that two of them may even hinder the construction of housing at prices affordable to the middle class.

I – Portugal Is Not Lisbon

In response to statements that “€2,100, €2,200 or €2,300 are not moderate rent levels,” the Government’s answer has almost always been: “Forgive us, but in Lisbon they are.”

Even conceding that €2,300 may be a reasonable upper limit for a moderate rent in Lisbon, how is it possible for that same amount to be applied across the entire country?

Is the Government unaware that — according to Statistics Portugal’s (INE) Local Housing Rent Statistics (referring to the first quarter of 2025 and published on 27 June of the same year, the most recent report available at the time of writing) — the median rent in Lisbon for new lease contracts stands at €16/m²?

And that in Braga and Coimbra — two of the most relevant cities nationwide — the median stands at €7.45/m² and €8.67/m², roughly half of Lisbon’s level?

According to Idealista, at the time of publication, fewer than 5% of apartments listed for rent in Braga are advertised at €2,000 or more.

In the municipality of Coimbra, again according to Idealista, there are only four listings (out of roughly 300 properties) at €2,000 or above.

There is no reasonable basis to justify applying a tax reduction to the construction of housing intended for rent that are unequivocally high in the contexts of Braga, Coimbra, and many other district capitals and mid-sized cities.

Applying the same benchmark to all 308 municipalities is equally inappropriate when defining €660,982 as a “moderate sale price” nationwide.

Economic agents respond to incentives. It is plausible to expect that, across much of the territory, part of the supply will tend to move — insofar as local conditions allow — toward that maximum threshold.

To gain a more objective understanding of these discrepancies, consider the Local Housing Price Statistics published by INE (referring to the third quarter of 2025 and published on 2 February 2026, the latest report available at the time of writing). The median price per square meter in Lisbon — with the exception of Porto and Faro — is roughly double or triple that of other coastal district capitals.

When looking at inland district capitals, Lisbon’s values can reach four or five times those of those cities.

The numbers are clear: in Lisbon, the median stands at €4,691/m².

In Viana do Castelo and Setúbal, it is €1,698/m² and €2,320/m², respectively.

In Guarda and Portalegre, the figures are €973/m² and €1,000/m².

On the Idealista portal, at the time of publication, it is possible to verify that:

In Marinha Grande and Pombal — two municipalities in the district of Leiria — the most expensive apartments listed for sale are advertised at €399,000 and €420,000, respectively.

The most expensive apartment in Castelo Branco is listed at €335,000. It is new construction, and the word “luxury” appears four times in the property description.

The most expensive apartment available in the municipality of Bragança is listed at €325,000, and it is the only one above €300,000.

I could provide another 250 examples of municipalities where it makes little sense for the State to incentivize construction up to the maximum ceiling of €660,982.

Most likely, the outcome of this decision will be the application of tax benefits to mid-to-upper segment new developments in Guimarães, Aveiro, Santarém, or Palmela — at the “moderate” values of Lisbon and Cascais.

For every developer, volume of investment and parcel of land allocated to projects involving €500,000 or €600,000 homes, there is one less company, one less tranche of capital, and one less piece of land dedicated to building apartments priced between €200,000 and €400,000.

Either the Government calibrates the criteria for granting the tax reduction, or it will end up diverting the incentive away from the construction of housing at prices accessible to the middle class, toward the production of prime-segment homes — a segment to which the market already responds organically without significant need for additional stimulus.

Consider the example of Vizta, which — through its Core brand — found solutions to offer a 31 m² studio (T0) for under €100,000 or 98 m² three-bedroom apartments (T3) for just over €300,000.

This residential development is being built in Leça da Palmeira, within the municipality of Matosinhos, the second most expensive municipality in the Porto Metropolitan Area.

The objective of this draft law should be to stimulate initiatives that generate housing in price segments similar to this project.

In its current wording, the draft law risks offering those who called for greater decentralization the one thing they do not want from Lisbon — its housing costs.

II – Why is the cap on rent (or price) the same for a studio (T0), a two-bedroom (T2), or a four-bedroom (T4)?

Even in parishes such as Campo de Ourique, Estrela, or Parque das Nações — where residential values are higher than in most of Lisbon’s 24 parishes — it is not true, for example, that €2,000 constitutes a moderate rent for a one-bedroom apartment (T1) with an area between 60 m² and 80 m².

The same applies to Foz or Porto’s historic center.

According to the Idealista portal, at the time of publication, there are more than 1,400 T1 apartments listed for rent in the municipality of Lisbon, fewer than 300 of which are advertised at €2,000 or above. What sense does it make to support landlords whose properties sit in the fourth quartile of the price distribution?

In Porto — again according to Idealista and at the time of publication — we would already be speaking of the 98th or 99th percentile.

The mismatch is not merely evident; it borders on the absurd. And it extends to sale prices as well.

Still, the budgetary cost of supporting rents that are not truly moderate concerns me far less than the tax incentive granted to the production of mid-to-upper segment housing. In that case, fiscal effort is diverted away from what the country most needs — housing accessible to the majority — toward a segment that the market already produces organically, without incentives.

In the case of sales, one might accept that €660,982 constitutes a moderate price for a T3 or T4 in Lisbon. But it is difficult to accept that the same could be said of a one-bedroom apartment.

If today I can find a development in central Lisbon, near Praça do Chile and the Metro, advertising 80 m² two-bedroom apartments (T2) with two bathrooms (one en suite), a 6 m² balcony and a parking space for €570,000 and €580,000, why should the State stimulate — via tax benefit — the production of studios or one-bedroom units at €600,000 or €650,000?

What prevents a real estate developer from maximizing the number of units eligible below the €660,982 threshold (thereby securing the tax benefit), opting for smaller typologies while charging significantly higher prices per square meter?

A developer might even argue before local authorities that the 2021 Census shows that, compared to 2011, the number of one- and two-person households has increased, while households with three, four, and five members have decreased. And that, overall, the average household size has been declining, while the number of adults living alone has been rising.

In all likelihood, that would be my professional advice.

Private initiative is fully legitimate in seeking to maximize the economic rationality of a project.

But it is the State’s role to prevent benefit-maximization strategies that divert the incentive away from the sphere of public interest.

It should be evident to everyone that within the same building, what may constitute a moderate price (sale or rent) for a three-bedroom apartment will, predictably, be exorbitant for a one-bedroom apartment.

If the Government intends to ignore this evidence, it should explain how such a choice benefits the middle class.

An 80 m² one-bedroom apartment sold for €600,000 corresponds to €7,500 per square meter. The latest median value recorded for Lisbon is €4,691 per square meter.

In other words, under the wording of Draft Law no. 47/XVII/1.ª, a property with a price per square meter exceeding the median value recorded in Lisbon by more than 50% may still be classified as a “moderate sale price.”

And, as we have already seen, it may be classified as a “moderate sale price” not only in Lisbon, but also in Vila Real, Oliveira de Azeméis, or Mértola.

If the previous example clearly corresponds to an expensive property, how can we accept a legislative solution that — with all the implications discussed — classifies its price as “moderate”?

A public policy that fails to acknowledge this reality risks losing its legitimacy.

III – Are We Going to Reduce Taxation on One-Year Lease Contracts?

Does it make sense to grant a tax discount to landlords who enter into one-year contracts that do not provide for renewal?

Landlords are fully within their rights to do so. But I question whether it makes sense to grant a tax benefit to those who offer no stability to the tenant.

Current legislation provides for the possibility of a 10-percentage-point reduction (from 25% to 15%) in IRS taxation for landlords willing to sign a five-year contract.

Are we now going to grant a 15-percentage-point reduction (from 25% to 10%) for contracts lasting only one year?

If family stability remains an objective, this tax design appears counterproductive.

Moreover, much has been said about encouraging built-to-rent (construction specifically for rental purposes). Institutional investors traditionally associated with this model favor longer-term contracts for reasons of cash flow predictability, risk reduction, and operational efficiency.

Considering that, regardless of the initial term, a landlord’s room for maneuver during the first three years of a renewable contract is already constrained by paragraph 1 of Article 1096 (Automatic Renewal) and paragraph 3 of Article 1097 (Landlord’s Opposition to Renewal) of the Civil Code, a three-year solution seems to be a reasonable compromise between the need to provide stability to tenants and the Government’s objective: broadening the number of contracts eligible for the tax reduction in order to motivate more owners to place their properties on the rental market. Indeed, this is what the same draft law already provides for under the simplified affordable rental regime.

If it is argued that such a solution would disadvantage tenants seeking only short-term contracts, it is important to recall that paragraph 3 of Article 1098 (Tenant’s Opposition to Renewal or Termination) allows tenants to terminate the contract after one-third of the initial term has elapsed, subject to 120 days’ notice — a prerogative not granted to the landlord.

If stability in residential leasing is a priority, the granting of tax incentives should be conditional upon guaranteeing it.

Conclusion

Recent years have been marked by successive increases in housing prices and by a widening gap between Portuguese household incomes and the cost of housing.

The draft law under consideration correctly identifies one of the constraints on access to housing: insufficient supply.

The use of tax incentives as a public policy instrument is, in this context, a legitimate and potentially effective option. It is also worth noting the broad fiscal scope of this legislative initiative: it represents a coordinated approach involving IRS, IRC, VAT, IMI and IMT, with the objective of making more housing available at moderate cost.

That said, some researchers argue that the outcome of reducing VAT on construction may not be a fall in house prices, but rather an increase in developers’ margins or in land prices.

One thing is certain: the effectiveness of any tax incentive depends on the precision of its design.

At present, the Government is classifying as “moderate” prices that are objectively high for most of the national territory. If nothing is amended in Parliament, a reinforcement of supply in the mid-to-upper segment of the market is foreseeable.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with that housing segment. But increasing its supply will not enable the bulk of the middle class to rent or purchase a home suited to their needs. For that reason, it is not the segment to which a tax benefit should be directed.

The Government cannot — and the expression is deliberate: cannot — claim that it seeks to promote the creation of housing units at prices affordable to Portuguese households while simultaneously deciding to grant tax benefits supporting the development of housing across the country at price levels that — as market data unequivocally demonstrate — correspond to expensive properties in most of the national territory.

The failure to differentiate value ceilings by typology is also difficult to justify.

It is one thing not to overburden real estate development; it is another to assume that the economic agent’s rationality, absent limits or reference criteria, will not undermine the Government’s purpose.

Because that is precisely what will happen. I have no doubt that the absence of clear criteria will encourage the construction of 60 m² one-bedroom apartments at the “moderate” price levels appropriate to 120 m² three-bedroom units.

Finally, granting the same tax treatment to one-year and five-year lease contracts removes the incentive for landlords to prioritize longer terms.

In doing so, it disregards the importance of stability in residential leasing — something that should be a priority in any public housing policy.

For this reason, the detailed parliamentary discussion of Draft Law no. 47/XVII/1.ª represents a decisive opportunity to calibrate and frame the measures appropriately. Introducing territorial differentiation, considering typology-based criteria, and aligning incentives with the objectives of contractual stability would strengthen the purpose of the proposal.

As might be expected, stakeholders have welcomed a proposal that grants them a tax reduction. Business associations represent legitimate interests and fulfill their role in defending them. It is hoped that both the Government and the media keep this in mind when analyzing the opinions of these entities and the statements of their representatives.

It now falls to the Assembly of the Republic to ensure that the final design of the incentive effectively serves the public interest.

If the ambition is to promote housing at genuinely moderate prices, rigor in the parameterization of the measures is essential to ensure that fiscal effort produces the intended impact.